[article by João Dos Santos, in Musical Traditions No 7, 1987]

Introduction

A close investigation of some musical traditions, from different parts of the world and apparently unconnected, reveals that they were, in fact, created by the same formative elements that translated into various forms of expression.

Anthropologist Joaquim Reis de Brito summarised, in a few lines, this phenomenon:

The parallels in the evolution of some musics are, in some cases, so obvious, that were it not for the specificity of the musical structure and/or choreography, and the diversity of ethnic elements, one could not guess at their respective identity.

Thus, if we take together the Fado of Lisbon, the Tango of Buenos Aires and the Rembetika of Athens, we will note firstly that all of them emerged a little before or after the middle of the 19th century in poor districts of the big port cities of the nascent industry, attracting people from the country or from abroad, and who were confined to a marginal existence. And if we look for other parallels in the development of these urban popular cultures, we will find them again: first, their obscure and repressed beginnings, then their discovery and appropriation by elements of the higher social classes, later their acceptance and admission by the establishment (often after their success outside of the native land) before ending as a subject of tourist explorations.

Surprisingly, most people writing about one or the other of these musics were, and are, unaware of these facts. The following article, by choosing numerous extracts from their works, is an attempt to show that, while they proclaimed the uniqueness of the genre which concerns them, what these people were relating is actually the same story in many, and parallel, ways.

(Note: All the books are written in the original language of the country concerned, except where stated).

The Origins of:

Rembetika

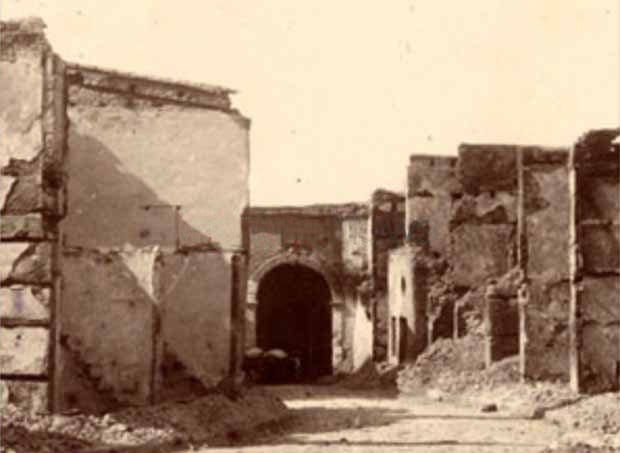

As far as we know, the story of Rembetika begins ‘towards the end of the 19th century, in a number of urban centres where Greeks lived’. The jails and hash-houses were the cradle of Rembetika. ‘In the prisons, instruments were made and songs were composed’. These songs became widespread among the world of the Rebetes (singular Rebetis) – the underworld – and, together with songs about hashish-smoking, were ‘already a form of Rembetika’.

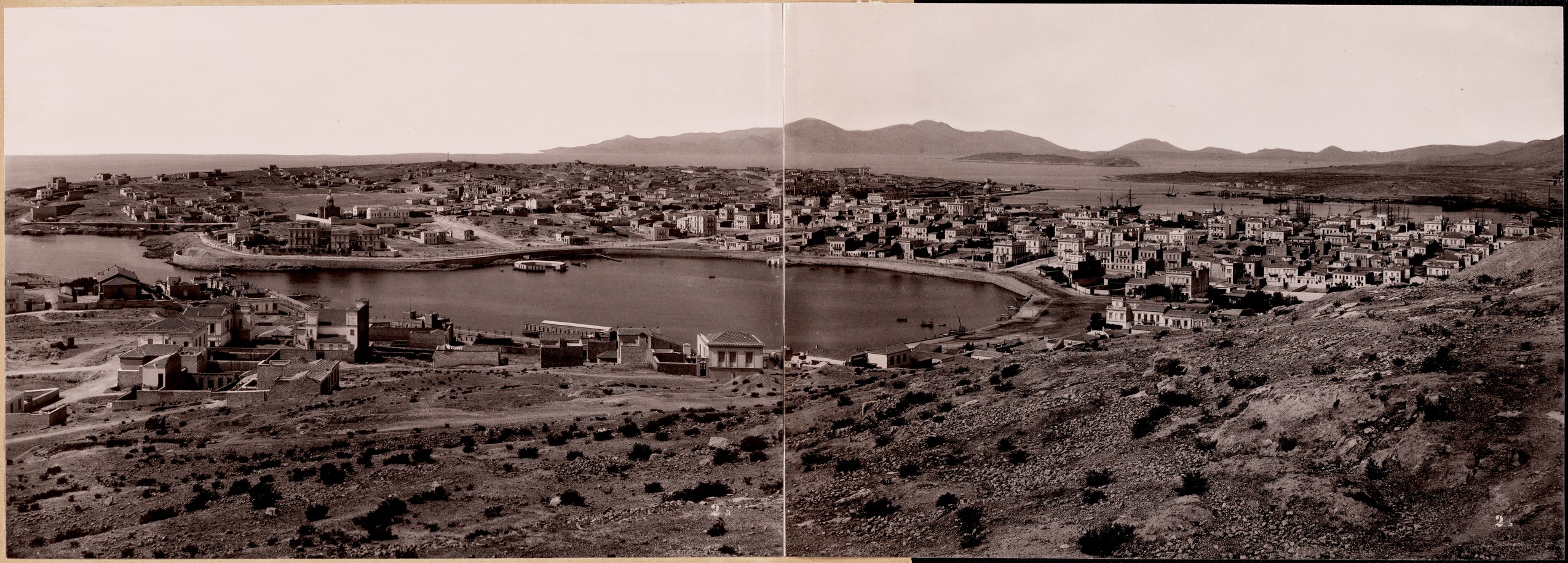

In 1922, as a consequence of the war against the Turks, 1½ million Greek refugees from Asia Minor went to live in Greece, mainly in the cities, where they exerted a strong influence on Rembetika. Now there were homeless, jobless refugees who swelled the total population of Greece by at least 25%. In a small underdeveloped country like Greece, this sudden influx could not possibly be absorbed without hardships … ‘The refugees may not have been part of the underworld, but … it was not surprising that many of them joined the Rebetes, or mangas, in their loosely organised subculture or were attracted to the hashish-smoking cafes to which they were accustomed in Turkey’. (from: Gail Holst, Road to Rembetika, 1975, in English.)

Tango

Argentinian author Jorge B. Rivera in his World in Transition (1976), dates the presumed origins of the Tango ‘around 1880, a key moment, in many ways for the understanding of modern Argentina.’

‘Men of the ’80s were suffering from the complex of the ‘deserted’ and so tried to raise the number of inhabitants by way of European immigration’. In Buenos Aires, where lived 181,838 people in 1869, the population grew, in 1895, to 663,854, of which 5% were immigrants. ‘There was a complex and contradictory relationship between the Creole (native) and the Gringo (immigrant) in an urban environment in full process of modernisation … When these men, often alone, were looking for distraction they went to dancing-clubs which served, more or less, as brothels as well, and which were the first settings of the Tango.

The Hermanos Bales (Bales brothers), in their History of the Tango of 1936 confirm that the Tango ‘lived in its infancy and a good part of its adolescence in very second rate dancing-houses … in whore-houses’.

A typical figure of the Tango of that era was the Canfinflero, or Compadre.

Fado

In his book Fadista Mythology (1974), Antonio Osorio writes that the Fado, in its definitive form, appeared in Lisbon in the middle of the 19th century, ‘in a time of great catastrophes in Portugal: the French invasion, the English domination, the revolution of 1820, the independence of Brazil and the civil war of 1832-1834’.

‘The Fado was born in a convulsed country, becoming poorer, devastated by successive wars … among the much oppressed classes.’ Osorio adds that the return of the Court in 1822, ‘with its suite of coachmen, bullfighters, gypsies … contributed in no small way to the favourable atmosphere for the appearance and the divulgation of the Fado.’

In 1923 a musicologist, G Sanpaio, describing the origins of the Fado wrote that ‘in 1833 existed, scattered in Lisbon, tavernas, later transferred, to safeguard people’s morals, to distinct quarters of the city’ and where fadistas were provoking disorder and singing a languorous song that they call Fado’.

The participants:

The Rebetis

According to Elios Petropoulos, co-writer of Rembetika (in English), ‘the rebetis was a person who lived outside the accepted standards of the traditional Greek Society and who showed contempt for the establishment in all its forms. He scorned work, helped the underdog, smoked hashish, bitterly hated the police and considered going to jail a mark of honour’

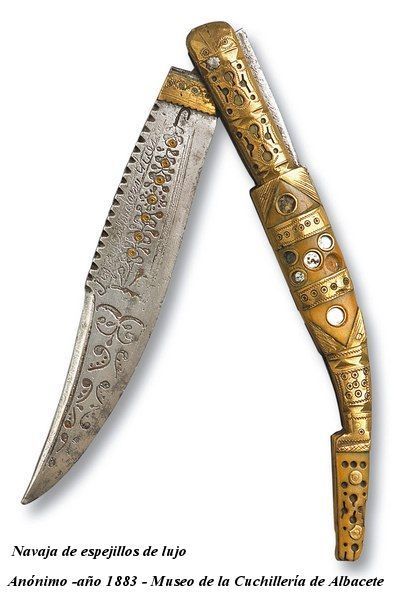

It seems the Rebetes made their appearance a little after 1821, when Greece received its independence from the Turkish Empire. They frequented specific neighbourhoods in Athens where they had their own tavernas and cafes. They controlled smuggling, the hashish market, the gambling clubs, and the whorehouses and trafficked in stolen goods. The Rebetes always had their own style of dress … tight trousers made in the best imported material, a dark collar-less shirt, usually black or purple, narrow pointed shoes with high heels and a fedora that was pushed far back on his head, or so far forward that he had to turn his head back to see … The Rebetis carried a knife or revolver in his belt and in his hand a cane made of hard cherry wood which he could use as a weapon in fights … He walked with a subtly arrogant manner … The police persecuted the Rebetes and the upper and middle class ignored them and wished they didn’t exist.

The Canfinflero

Historian Jose Gobello, in The Origin of Tango Lyrics, states ‘the canfinflero was not an industrialist of the woman trade. He exploited generally only one woman, sometimes two’. Manuel Galvez gave the following portrait of the canfinflero:

He dresses in an original way: A black suit, tight trousers, a silk neckerchief, a trilby with a tilting brim and a pair of pointed shoes.

The canfinflero is dangerous. Of an impulsive aggressiveness, he seeks fights for tiny reasons. He is devoid of any moral sense’. Insensible to punishment and pain, he spends in card games the money given him by his ladyfrlend for whom he feels no affection. He beats her, insults her, requires money from her, robs her … All this kills the tenderness of the woman – faithful as a dog that the well-loved master punishes.

As we have seen, the Tango was first played in brothels, mainly as an instrumental music. When it was sung, the words did nothing more than reflect the surroundings that gave them life: obscene or arrogant. In a tango by Angel Villoldo, the canfinflero describes himself in this way:

I feel no pain, nor offence

And don’t complain about my fate

To live it up I was born

And so I’ll do until death.

The Fadista

Of this new social category, the Fadista, Ramalho gave, in 1878, a colourful description:

In no other city of Europe exists a word with a meaning such as this: the Fadista. To be a fadista signifies to be a tolerated criminal assembled with others of his kind, constituting a class … The fadista lives by the exploitation of his neighbour. He is usually fed by a prostitute that he exploits systematically. He has no regular address, living successively in a tavern, a brothel or a Police station. He is totally atrophied by idleness, by sleepless nights, by abuse of tobacco and alcohol. He is anaemic, stupid … and is possessed by a secret disability and various parasites of the skin.

Even a great lover of the Fado, Tinop, in his History of the Fado, written in 1903, said, ironically of the fadista of his time, that he is

‘an heteromorpheous product of all vices’, attaining ‘the ideal perfection of ignominy … Psychologically, he is the crystallisation of all the deadly sins except miserliness – and an abject scoundrel. His life keeps on being a constant melodrama with unexpected Coups de theatre … A wandering bohemian on the borders of a stable society, his hereditary defects continue to be irriductible to the surveillance of the police and to the coercive action of tribunals. His loves are always selected from the women who lived, and live in the microbian atmosphere of the infamous districts.’

When it was still confined to this sordid world of fadistas the Fado was associated ‘with the name of Maria Severa, the ‘soul’, the ‘mother’ of the Fado and, until today, the most important myth the Fado has known. The illicit love affair of Severa – mezzo-soprano of the conservatories of vice’ (Tinop) – with the Count of Vimioso ‘has inspired many verses and is at the origin of the aristocratisation of the Fado which spread, little bit little, from the middle at the 19th century, in all the social classes, mostly in the cities’.

Manuel Barreto in Fado: Lyrical Origins and Poetic Motivations written half in Portuguese, half in English, in the ’70s, recalls:

Together, arm in arm

Back to the past we went

More than a century ago

When Severa and Vimioso

Were cause for scandal together

And the Fado was still in its youth.

Aristocrats and singers

Whose behaviour caused concern

And shocked the bourgeois class

For daring to be fadistas

And rowdies, sometimes, too.

The Count of Vidigueira

Would come from ‘Lus de Pedreira’

To fetch the Marquis of Belas

And then, with Castelo Melhor

They’d do the rounds of the Fado

In taverns and narrow streets.

The word Fado, it must be said, is derived from the Latin fatum meaning Fate, Destiny, what has been foretold by the Oracle and which nothing can alter:

You cannot flee

From your fatal Destiny

That an ill star dominates.

You can lie

To the laws of your heart

But, Ai!, whether you will or no

You have to comply

With what is written. [Amadeu do Vale]

The Fadista: ‘Eyes half-closed, a tense face, as if in a trance, an air of deep mourning, and, as if not enough, the gravity of a long black shawl … the accessories of misfortune are few but well worked out …. [A Osorio]

Rembetika

Another description from Gail Holst: ‘the Rebetes were the drop outs, the nonconformists of their day … They could be jailed, beaten, chased out of town, but they would continue to live the mangas life, speak the mangas language, wear the mangas clothes. And it was this refusal to be brought into line with the mainstream society which caused him to be feared both by the representatives of established authority and by the representatives of organised opposition’.

Sakis Papadimitriou adds in Rembetika: ‘The Rebetes spoke and still speak their own argot, which is exceptionally rich in expressions and hand gestures. The womb of Rembetika was the jail and hash-houses. It was there that the early Rebetes created their songs. Rembetika does not long for social change or urge revolt and this is why the Greek Left has ignored its existence … They were considered the immoral songs of drug addicts, prisoners, the poor and uneducated. For this reason the middle and upper middle class as well as any other form of establishment did not accept the Rembetika and indeed held it in contempt’.

For Gail Holst again, the songs of the Rebetes ‘reveal a reliance on fate to control and excuse their actions’ while Gerard Pierrat in Mikis Theodarakis (a book written in French), will say that the Rebetis ‘is not able to imagine the upheaval of Society, refuses it and substitutes escapism for revolution’.

Tango

Jose Sebastian Tallon in The Tango in its Stage of Prohibited Music (1959), mentions that with Pascal Contursi, the first poet of the Tango, ‘The canfinflero opens his heart for the first time to expressions of sorrow’, in the tango Mi noche triste (my sad night) of 1918, the first tango-cançion or tango with a story.

Jose Cobello confirms:

While the compadre of Villoldo didn’t know suffering, Contursi, in his tango Mi noche triste, (sung by Carlos Gardel), and others that followed like Flor de fango and Ivette, inaugurated the theme of the canfinflero who weeps, deserted by his companion. The first tangos of Caledonio Florès – another poet of the Tango – Margot, and Mano a Mano described the same characters and situations.

Interestingly, these tangos were sometimes sung by women, like Azucena Maizani, the interpreter of Malevaje:

Yesterday, afraid of killing –

Instead of fighting

I started to run away.

I thought of seeing you no more

And I trembled.

If I, who never feared,

Anguish by night, burst into tears –

Say, for goodness sake,

What have you given me?

I am so changed

I no longer know who I am.

In later years the content of the songs moved beyond the restrictive world of delinquency and compadres, but always kept melancholy and nostalgia as essential features. (Incidentally, Europe never understood the dramatic content of the Tango. Here, the Tango is seen as an easy-listening type of music, which it never was in Argentina. Only in recent years this grave misconception has begun to disappear thanks to, among other things, the work of exile Argentinian musicians.)

Fado

Pain, Sadness, nostalgia!

To sing, both by night and by day

Is what is written, my Fate! [Dr Antonio de Braganca]

While a fadista today denotes a interpreter or a lover of the Fado, and not necessarily a hoodlum, this fatalism, so prevalent in Fado lyrics has caused him to be fought, from early on, by people psychologically unable to understand his philosophy of life. ‘The Fado is resignation, conformism at the extreme, apathy, total renunciation: the question is not to be happy or unhappy but to accomplish the Destiny for which one is born’ says Osorio, for whom the often-made comparison with the Blues is not even valid: ‘Sure, there are some parallels: the blues was also born of a state of ancestral subjection, but the pain which is expressed in the blues, doesn’t constitute, generally, as in the Fado, this labyrinthine form of resignation. ‘My only sin is my skin’ says Louis Armstrong and many blues singers whose singing is a war cry against their own subjection’.

Tinop, who made a detailed study of his clothes said of the Fadista of 1850 that he had:

The innate idea of Bohemian elegance. He wears a long jacket with a woollen cloth handkerchief in the pocket. The buttons are made of pearls, while the shoes, from the skin of a frozen kid, have laces of black ribbons. He also uses a cane made with reed from India, swinging it tightly held between the middle finger and the forefinger, waddling with some air of bravery. The smart guy … Some wear the jacket on the left shoulder, so they can parry the blows with it, while releasing the right arm for attacking with a knife that they handle with virtuosity, leaping with the feline gymnastics of a tiger.

The Years of Controversy and Contempt

Rembetika

It may be a slight exaggeration to say, as Petropoulos does, that ‘Rembetika was once considered as dangerous as leprosy’, but it is true that the songs were credited with a surprising power to influence people.

In the pre-war period, Rembetika songs were banned, bouzoukis and baglamas smashed by the police, even the dancing of Zebekiko forbidden. Less understandable was the attitude of the Left, or more specifically of the Communist Party, to Rembetika. In an article in the literary periodical Epitheorisi technis in 1961, Tassos Vournas described Rembetika as the art of the oppressed masses, saying that ‘it encouraged people to submit and sought to bind them in a vicious circle’.

In the same year an interesting inquiry was held in the left-wing newspaper Avgi, where people of the musical and literary world were asked to state their opinions about Rembetika. One or two were enthusiasts but the majority condemned Rembetika as ‘impure, musical slang, decadent, irresponsible’. Arkanidos went as far as to say that he had warned the Greek intelligentsia in 1949 about the power of Rembetika, but excused composer Theodorakis (then a Communist) for using Rembetika elements in his compositions because they were ‘part of his personal creation’ – [Gail Holst]

Even today, as Gerard Pierrat reminds us, ‘it is common in those who recognise the importance of Rembetika and have become its more ardent propagandists to pretend to disassociate the words from the music. That is the case of Theodorakis who calls the music ‘genial’, ‘divine’, while he judges the lyrics as ‘vulgar, without interest’.

Until the first recordings of Rembetika were made, it was more or less tolerated ‘but with the divulgation of the songs, it was another story! What was at stake was the health of the Nation and notably of the working class’. Rembetika musician Markos Vamvakaris remembers:

You have no idea of the general outcry that the bouzouki created in that time. It was an instrument which was played by criminals, by people sentenced to die. Today, anybody can touch its strings without further thinking. Me, when I hold one, it’s a sacred thing. For it has survived the worst ordeals. That was the reason the police were against it and against me also. They were afraid of the contagion. Such was the power of bouzouki.

War and occupation of Greece by the Nazis lead to an extreme misery and repression:

The future seemed to promise only disaster and death. And what else has the Rebetis done for more than 20 years, than to anticipate, in his songs such an apocalypse? It was not he who had caught up with events – for which he continued to manifest a superb indifference – it was the events which came to comfort him in his fatalism; his intransigent pessimism. The circumstances, hard as they were, his triumph could only be modest, but his prestige grew secretly’ [Gerard Pierrat, Mikis Theodorakis]

Tango

This shameful birth, this patronage of tough-guys and of regulars of the night, men as much as women, made the Tango a prohibited dance – and more – a dirty word that no-one should pronounce if he pretends to be decent. The high classes were horrified if someone mentioned it, if someone dared talk of this heretical music … But it is necessary to mention that the problems of the rejection of the Tango were not only those of the high classes; we say that any family which claims to be respectable would close its doors to it, and we include in this those of the middle and working class as well – [Ruben Pesca, The Old Wave]

‘The Tango had yet the infamous presumption of a brothel dance, for scandal of the families. To dance it was, in some way, to contaminate oneself with its origin’ – [Leon Benaros, The Tango in the Dancing Houses, 1977]

One who was horrified by the Tango was Carlos Ibarguren: ‘an illegitimate product that has not the natural grace of the country, it is not properly Argentinean but a hybrid phenomenon born in the suburbs and consisting of the mixing of a tropical habanera and a falsified milonga’. Famous band leader Julio do Caro, at the beginning of his career, was ejected from his home when his father, a music professor, discovered that his son was a Tango musician.

Curiously, after the Tango became deep and serious (after Pascal Contursi) there were some who would still condemn it, for being too moaning, and regretted the carefree liveliness of the old Tango. Indeed, the world of the new Tango is nostalgia:

Going back with pain, with melancholy, to things of the past; no matter what past, as long as it is past. Because the Tango was not made for singing what is owned, but what has been lost. The Tango, by essence belongs to the elegiastic genre [Jose Gobello, Enrigue Delfino and the Tango-cançion]

Fado

The most violent attack that the Fado suffered in the last century was by Rocha Peixoto, in his book Portuguese Country (1897), where he accused the Fado of being the ‘crystallisation of the evils of the Nation’, among other epithets. In 1909, Antonio Arroio, in an extensive study, also violently condemned the Fado, judging it ‘a true national calamity. It expresses the state of inertia and sentimental inferiority to which our country was attracted many years ago, and from which it is urgent that it gets out’.

In the same year happened the Republican Revolution of the 5th October. Shortly after, in 1912, the hostilities against the Fado were re-opened, without success. In reaction to these negative statements Avelino de Sousa published The Fado and its Censors: a critique of the detractors of our national song, where he argued with men like Samuel Maia (who described the Fado as ‘abject, disgusting’) and Albino Forjaz:

The ‘Albino’ lacks authority to attack the national song, for the Lord Forjaz, when he frequented, in his youth, the Taverna do Alfaia, was known to sing furiously the Fado. So, this ‘fadista colleague’ is a renegade for writing that the Fado is a song of vagrants or a gathering of criminals.

In 1929 occurred a moment of crisis for the Fado: Luis Moita, in eight conversations on the National Radio, engaged in a campaign against the ‘moral and musical misery of the Fado’; conversations later reunited in the book The Fado: Song of the Vanquished (1936) where he urged his compatriots to reject the influence of the Fado and to fight it ‘nobly, with their virile enthusiasm’.

Luis Moita launched the war with the hope that in the reconstruction of Portugal the Fado would be abolished. Dozens of fados of that era show the indignation that his campaign gave rise to:

They even call the fadistas

Ruffians of the pure school

But tell me, moralists

What has more terrorists

The Fado or Football?

With a superior disdain, the Fado rejected the comparison and the competition with the ball. For the fadistas, despite their attraction as the blackguard, always claimed to be ‘artists’, suffering poets; The Fado consists in a vocation as noble as it is irreversible and for this reason, when its enemies accused it of decadence the lovers of the Fado moved to the counterattack.

Again the prestigious co-operation of intellectuals was not lacking. A Vitor Machado wrote The Idols of the Fado where were compiled the pro-fado reactions that the attack of Luis Moita. In the preface, Artur Ines declared: I like Fado because it is the ‘escape livre’ – the free escape of the people. It is the song of the sad, the poor, the deserted, those who suffer. To remove the Fado from the people would be to take away its only valvula of respiration.

The same kind of argument was used by Ramada Curto: ‘the social drama that the Fado reflects reveals itself more tragic and inhuman in other countries, because they have not the magical solution, the consolation of a guitar that weeps and a voice that rises, sweet and sad, to sing of fatalism and destiny’.

But without doubt the most definitive rehabilitation of the Fado was due to Antonio Botto – the famous writer – who, from his position of authority, wrote verses meant to be spoken ‘at the guitar’.

Triumph and Decadence

Rembetika

In 1949, composer M. Hadzidakis gathered musicians Markos (Vamvakaris) and Tsitsanis in a conference where he proclaimed to the Athenian high society that the two gentlemen, wisely seated on the platform, were nothing other than the Bach and Beethoven of laika (city) music. A delicious shiver ran through the audience. That was just the beginning of recognition for Rembetika.

The worldwide success of the film and the music of Never on a Sunday did more to convert the bourgeoisie than all the campaigns at home. If New York, London and Paris placed the bouzouki at the top of their hit parades, hesitations were no more permitted.

‘A new craze soon was all the rage: Going to listen to the bouzouki in the typical districts where it was traditionally performed. The pioneers witnessed with amazement this earthquake. They were not able to resist for long. It was their turn to move from their joints to go playing, for fabulous sums, to delighted mundane audiences. The old melodies soon mixed with the smell of kebabs and retsina’.

From 1955 on, bouzouki competes with the Acropolis and Mycenæ. Patiently, bus drivers wait behind the door of the taverns before talking back their stock of tourists, filled with exoticism … The genre moved toward light music, creating one-day idols. The orchestras were now composed of 2 or more electrified bouzoukis, 2 baglamas, 2 guitars, drums, a bass, a piano, a harmonium. Electronics and psychedelism gave it the ‘finishing blow’. Customers would break plates and burst baloons, while a waiter quickly adjusted the bill. A true disaster!

But, we mustn’t scandalise too soon: this caricature that Rembetika gives of itself is the more eloquent form of suicide. In such an outrage to deny all that it was, one cannot help thinking of this old gangster turned, later in life, into the manager of a respectable hotel. And cursed be the stranger who comes to remind him of the past! Prison? Hashish? The old damnation? All that is very excessive!

In an interview given to me by singer Sotiria Bellou, she insisted on this one point: the audience of Rembetika was composed, from all time, of what she called ‘the cream of society’. At least the new generation has well understood. One has only to see the fervour it puts to save the old recordings, to find again the original purity, its rejection of all adulterated airs – [Gerard Pierrat]

As Markos Dragoumis declared, in Rebetika: ‘The old genuine Rembetika music is unique … When you hear this music, you feel that something very deep and important is taking place, that you are encountering one of the great achievements of the human heart’.

Tango

The evolution didn’t concern the middles and high classes. Here the Tango continued not to be talked about. But something unexpected was ready to occur; the high society of Paris was tired of the old dances. It was necessary to try something new. The Tango – intact, attractive, exotic, different, was the perfect candidate. Paris was going to dance the Tango, which soon triumphed in the capital cities of the whole of Europe. Not all Argentineans – in fact, only a few – accepted without reserve that it was just this expression of marginal people which would claim for itself any attribute of national representation – [Horacio Ferrer, The Book of Tango, 1977]

A magazine with a very limited circulation, El Hogar, would comment:

As it is known, the aristocratic society of the French capital have adopted with enthusiasm a dance which, here, because of its very bad tradition, is not even named in the homes. Will Paris manage to make accepted in our good society the Argentinian Tango? Probably not – while Paris, so capricious in its fashions, will do all which is possible for that.

The journalist, of course, was wrong, and good society would soon open its doors to the Tango, and now ‘with an irreversible enthusiasm, the entire city repeated the verses of the Tango all morning all afternoon and all evening. It was a collective fever, as if the people, living until then unaware that they have heart, have just discovered it’ – [Francisco Garcia Jiminez, The Tango: a history of half a century , 1964]

One fine example is the well-known tango Tiempos viejos (Old Times)

Do you remember, brother, the fair Mirella

That I took away from the valiant Rivera?

One night I almost committed suicide for her

And today, she is just a pitiful beggar.

Do you remember, brother, how lovely she was,

We used to make a circle to watch her dance.

When I saw her the other day, so old in the street

I turned my head away and started to cry.

Dario Canton observes: ‘Fatalism predominates in the Tango. The idea of man as a creature of initiative, able to modify the world which surround him, is foreign to it. Destiny is almighty and ever present’.

What helped the Tango to spread beyond its birth place was a mechanical instrument:

Another mechanical process for hearing music was the phonograph. The record industry saw the Tango as a possible commercial product, mainly for dancing houses where records could reproduce the music for less money than was needed to pay musicians – [Ruben Pesca, The Old Wave]

In the mid-fifties, began the alteration of Argentinean society and the decadence of the Tango. Jose Gobello in Talking about Tangos, (1976) gives a subtle explanation of this phenomenon:

The Tango seems to start from the notion that human nature is perverse, that Man is bad at heart … and, in front of this perversion, it puts forward ethical values. At best, the decline of the popularity of the Tango is a result of the decline of ethical values. In an age of generalised divorce, fidelity means nothing much. In an age when one is killed from behind, physical courage looks antiquated. In an age of generational gaps, the viejita, the poor old mother of the Tango, is only a fantasy. And the Tango, which expresses these values, which exalts them, has of necessity to suffer the fate of all obsolete things …

Some believe that the Tango must abandon this category of values to adopt those in fashion, the social or ideological values as expressed in some modern songs, very successfully and profitably. I don’t think so. I think that after praising loyalty for so long, the Tango has the obligation to be loyal to itself. Some day it will receive the reward for its faithfulness, because Man, sooner or later, will understand that it is not the system which makes us better or worse, it is ourselves who make the system better or worse.

Fado

Since the attack of Luis Moita, the Fado became ever richer and victorious. From ‘song of the vanquished’, it passed to be, in fact, the ‘national song’ of Portugal before ending up as one of our tourist attractions – [Antonio Osorio]

This commercialisation gave birth to lyrics of nostalgia for the Fado castigo (pure, classical) as can be heard on a record in the form of an humorous dialogue between two singers (a desgarrada).

female voice:

I am the new Fado

I don’t like fatalism

You will see me in the winter

I am part of the tourism

male voice:

But I am the old Fado

My tone is husky

Come and learn to sing with me

So you will know what Fado is

female voice:

As for singing

No-one can teach me

I am so much in vogue

And frequent only

Well mannered persons

The ’60s increased the number of these Fado houses, or casas tipicas, and often, the one time bastions of Fado became in reality, bastions of tourism:

You wish to hear the Fado

At quiet hours, with guitars and women

And, after getting drunk

Clap your hands

Knock with knives and forks

Upset the wine glasses

Then break all the crockery

To the sound of Ai! Mouraria!

But if you like a ‘Fadhino’

Then listen!

If not, stop that craziness! [Frederico de Brito]

As Mascarenhas Barreto said: ‘today the Fado, victim of the lucrative aim of the tourist policy, commercialises itself. Some of these casas de Fado have also folk dances and songs, it is necessary to discern where begins and where ends the Fado!

In conclusion, I will quote anti-fadoist Antonio Osorio – responsible for much of the information included in this article:

Side by side, in the same barricade were reunited by the caprice of the occasion an Artur Ines and a Vitor Machado, a Carlos Amaro and a Ribeiro dos Reis, a Ramado Curto and a Màrio Saa, men of opposite political ideas – because the Fado, joining, when it is necessary, the left with the right, has the virtue to put everything in confusion.

– João Dos Santos, Musical Traditions No 7, 1987

Είπε πρόσφατα ο φίλτατος Σαραντάκος (

Είπε πρόσφατα ο φίλτατος Σαραντάκος (